When Kate Zernike ’90 broke the story of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)’s admission in 1999 that it had discriminated against women on its faculty, it was news. Not only because Nancy Hopkins and 15 other women used science to prove their systematic marginalization by MIT in a groundbreaking report, but also because MIT acknowledged the truth of that report.

At the time, Zernike was a reporter with The Boston Globe. The story went viral as women saw themselves and their experiences reflected in the experiences shared by Hopkins and her colleagues.

For Zernike, though, the story didn’t have the same personal resonance. Her own career was on the rise and she hadn’t faced the same barriers Nancy Hopkins’ generation had. Times had changed.

Finding her path at Trinity

For Zernike, deciding to go to Trinity was in part inspired by her mother.

Barbara (Backus) Zernike ’54 was a proud Trinity alumna. Zernike and her older brother, Frits Zernike ’86 grew up hearing their mother’s stories about her College days and her continuing bonds within the Trinity community. “It would not be an exaggeration to say that of all the interviews I’ve done, this one would be the one that mattered most to her,” says Zernike.

She remembers driving up from her Connecticut home with her mother in early September 1986, and arriving at St. Hilda’s. She studied English and History, “which, looking back, was great training for journalism because you read a lot, and history develops the context.” But her interest in a journalism career didn’t start until her third year.

“I never really ventured out into the larger U of T community until my senior year,” she says. Once she did, however, she successfully ran for editor of The Newspaper and ended up staying on as one of three editors for a year after she graduated.

Seeing a pathway for herself, Zernike completed her Masters at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in 1992. Next was an internship followed by a full-time gig at The Patriot Ledger, a daily newspaper in Massachusetts. In 1995 she moved on to The Boston Globe.

Oh, and there was that Nobel prize

Although she doesn’t offer up this bit of family legacy, Zernike is clearly proud when asked about her grandfather, Frits Zernike, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1953 for his invention of the phase-contrast microscope. Her father, too, was a physicist, and she knew from his stories how few women there were in the field.

In fact, it was her father who first suggested that Zernike write about the work being done by a woman at MIT to get more women into physics. At the time Zernike didn’t see an urgent story there: “I thought it was a problem just in physics,” she remembers.

Then she received a tip in 1999 to call Nancy Hopkins, a molecular biologist who was a professor of biology at MIT, a leading cancer researcher, and known for her lab that used zebrafish to study genetics. She learned from Hopkins that the president of MIT was going to admit that the university had discriminated against the women on its science faculty. This, Zernike knew, was news.

The story ran on the front page of The Boston Globe in 1999 and within days, it reverberated around the world.

The dream job

In 2000, The New York Times called. It was the move Zernike had been working toward, and she joined the newly expanded education desk. She later moved to the investigations desk, and was part of the team that won the 2002 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting for stories about al-Qaeda before and after the 9/11 terror attacks. She also co-wrote Osama bin Laden’s obituary—nearly 10 years before his death. It was one of a number of stories Zernike was asked to work on in November 2001, and when bin Laden was killed in May 2011, the 4,000-word obituary ran on the front page of The New York Times.

She went on to the national desk, which had been her “dream job.” She has since covered Congress, metro, health care, and politics for the paper. She wrote her first book, Boiling Mad, about the origins of the Tea Party movement in the U.S., on a six-week leave from work while juggling motherhood of an infant and toddler.

Writing The Exceptions

In 2018, MIT called. Nancy Hopkins had retired and was trying to decide what to do with her extensive papers from the time of the 1999 report. There was talk of a book, and Hopkins wanted Zernike to write it. Twenty years had passed, and Zernike found she could relate on a more personal level to the kind of systemic bias Hopkins had documented. “I started to notice it around the time I was expected to get married and have children. There was an assumption that you would no longer be as engaged with your career, which is not at all how I felt.”

And after she had her children, Zernike recalls having assignments scaled back. She was on the presidential campaign trail and asked an editor why it seemed like her stories kept being absorbed into someone else’s rather than running under her byline. He told her he had noticed the same thing, and when he’d asked others, he said, “I was told you couldn’t travel.” No one had actually asked her.

With the book, she says, “I saw an opportunity to show how 21st century discrimination works, how it happens so subtly that often the women who are experiencing it don’t recognize it at first. In Nancy’s case, it took her 20 years.” Zernike spent the next three years writing the book. In the process she learned about the universality of Hopkins’ story for herself and so many women.

Sparking conversations

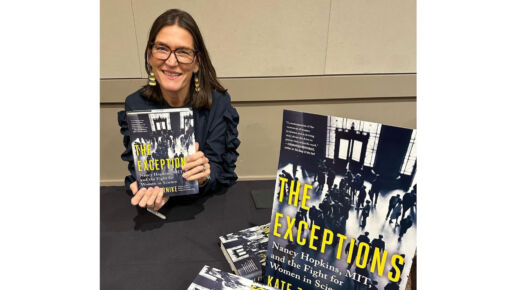

Since its release in February 2023, The Exceptions has been named on multiple “best of” lists for the year, and was one of six shortlisted titles for the 2023 Royal Society Trivedi Science Book Prize.

Women of all ages continue to share their experiences with Zernike as she speaks at events across the country. “There’s definitely been a generational response,” she says. “Women older than me appreciate how hard women fought and how far we’ve come. But I’ve had young women—scientists and students—who are saying we’ve got much farther to go. They want to know how we’re going to fix things now.”

“My grand hope is that in better understanding the context of where we’ve come from, people might be able to have the conversations about how we change this world. How do we change the system in a way that is fair to everyone?”

Those Trinity ties

Looking back to her College days, Zernike remembers getting ready for Conversat, fiercely debating in The Lit, stage-managing a Trinity College Dramatic Society production of The Crucible (and standing in for one of the actors at the last minute). But she adds, “when I think about Trinity it’s not so much about the events, it’s about the people I was with.”

Like many alumni, she has maintained friendships from her time at Trinity, including with Tassie Cameron and Pam MacKinnon, who she visited while on book tour in San Francisco. “I was friends with people in all different years, and I loved that.” She continues to have plenty of chance Trinity encounters, too.

This past summer, she interviewed fellow alumna Eliza Reid ’98 at the 2023 Montclair Literary Festival (“we learned of our Trinity connection just before our conversation,” says Zernike). In the fall she spoke at a pharmaceutical company, and there “ran into a Trinity classmate who runs their clinical trials. Her husband, also our classmate, did his PhD in the Harvard lab of someone mentioned in my book, who worked alongside Nancy Hopkins. Trinity connections are everywhere.”

–by Jennifer Matthews